Q2 2016: Rate Hikes Proved Challenging

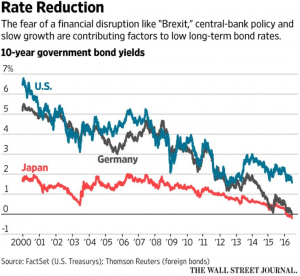

While the financial markets produced modest returns for both stocks and bonds through the first half of 2016, the markets did provide plenty of excitement for those engaged in the daily drama. Britain voted to exit the European Union in late June, causing a sharp selloff followed by a more violent recovery that brought markets back to where they were before the vote. Interest rates started the year at elevated levels in anticipation of interest rate hikes that never came, providing a tailwind for fixed income investments. Commodity prices plummeted early in the year then moved higher into the end of June. When the first half bell rang, the stock market, as measured by the S&P 500, had edged up 2% year to date. We continue to believe that the most significant factor for stock and bond returns in 2016 will be US interest rate policies, and therefore want to devote this commentary to discuss the current economic backdrop and the implications for future policy actions.

At the start of 2016, it was widely believed that the Federal Reserve would continue to raise interest rates at its policy meetings throughout the year, with several Fed Governors projecting that they would raise rates four to six times this year. Then last month, a shockingly weak May jobs report knocked the Federal Reserve back to the sidelines, triggering fears that the economy was too weak to handle higher rates. Market pundits offered that the Fed had once again missed its chance to raise rates. For the past two years, the Fed has charted a path to steadily raise interest rates, but the Fed has repeatedly pulled back because the economy suddenly weakened, inflation dropped, or the financial market volatility spiked.

The Fed still thinks rates will gradually rise as unemployment falls, which leaves it looking for windows of opportunity to raise rates. Critics contend that the Fed has boxed itself in: By communicating to the market that it intends to raise rates, the Fed triggers conditions that make it impossible to follow through. However, this logic is not entirely accurate. It implies that the Fed tightens only when it can, not when it should. This confuses the tool of monetary policy, interest rates, with its goal, which is low unemployment and stable inflation around 2%.

The Fed’s rate target was near zero from 2008 to 2015 and, after just one increase, sits between 0.25% and 0.5%. Because it is so low, it might seem self-evident that rates have to rise. After all, isn’t that what the Fed believes, with its dot plots tracing out a steadily rising path for the Fed funds target? Perhaps the Fed has reached a new conclusion; perhaps it now believes that the right level of rates will have been achieved when the economy is at full employment and inflation at 2%. It could be that the Fed has come to accept a “lower for longer” approach to interest rates. A few years ago, Fed officials thought that the normal interest rate – they prefer the term “neutral” or “equilibrium rate” – was 4%. Now they think it’s 3.3%. In a speech last month, Janet Yellen, the Fed chairwoman, suggested it may now be less than 2%. The truth is, these are all guesses. For all they know the right number is 0.25%. No economic law dictates what Fed funds rate should correspond to a fully employed economy.

There are two reasons why the Fed might wish it had raised rates sooner. One is if inflation quickly rises past its 2% target, requiring a much more dramatic tightening and possibly recession to get inflation back down. That looks exceedingly unlikely. In fact, long-term inflation expectations, already below 2%, are dropping further. The other reason why the Fed might regret not raising rates is that the prolonged period of zero interest rates feeds destabilizing financial speculation, which eventually reverses, violently, leaving the economy worse off than if the Fed had tamped things down sooner. This second concern is not a trivial risk.

The right response is for the Fed to weigh the benefits of keeping rates low, which are higher employment now, against the costs, which is a slightly higher probability of a large loss of employment later.

In 2014 that tradeoff may have favored moving rates higher, as markets were quite frothy. Since then, the mere expectation of tightening has cooled risk-taking, and that is probably why the economy, with a lag, has slowed. Last month, Chairwoman Yellen indicated that notwithstanding May’s lousy jobs numbers, she thinks the labor market will continue to strengthen. While she was proven prescient when the June employment report came in strong, the risks of a recession have still risen recently; according to J.P. Morgan, the odds of recession in the coming year have risen to an uncomfortably high 36%. If in fact a recession comes to pass, the Fed will be glad it didn’t tighten even more.

The other important consideration for US interest rates is its effect on the US dollar versus other global currencies. When the Federal Reserve raised rates last December, it seemed to think that the fallout would be minimal. After all, it had telegraphed the increase for a year, and it was just a quarter of a percentage point. However, since it raised rates, both the US and even more so the global economies have slowed. The reason for the slowdown isn’t simply because a quarter-point rate increase by itself represents a stringent tightening of monetary policy. Rather, the rate hike brought to an end seven years of unprecedented monetary ease that had helped fuel a global commodity bubble. That bubble began deflating in 2014 and the effects are now being felt around the world and washing back on the US. While the Fed had seemed intent on raising rates again in coming months, the weak May payroll report raised questions about the health of the US economy.

But it’s not just the trajectory of the US economy that should guide the Fed’s decision. While the Fed is the US central bank, the dollar’s central role in the international financial system means it also is the

world’s central bank, and the world may not be ready for another rate increase. In theory, the influence of the Fed on the world economy should be receding, not growing. After all, the US’s share of global output has shrunk, as has the number of countries pegging their currencies to the dollar (China is a notable exception).

Yet today the US dollar is now more influential than ever. According to a report by Morgan Stanley’s chief global strategist, Ruchir Sharma, the US dollar accounts for 87% of currency transactions, 60% of global reserves and 62% of cross-border debts. Oil prices are supposed to respond to supply and demand but nowadays they also respond to the dollar, he says, because trading of oil far exceeds actual consumption, and trading is conducted in dollars. Similarly, the Bank for International Settlements has found that when the dollar is weak, dollar loans are plentiful, but when it rises, the supply shrinks. “The global banking system runs on dollars,” said Hyun Song Shin, the BIS’s research chief.

The Fed responded to a collapsing housing bubble in 2008 by cutting interest rates to near zero and beginning to buy bonds. It had the desired effect in the US, by bringing down unemployment and warding off deflation, but unintentionally helped create a new bubble abroad. Commodity prices had already been climbing sharply for several years on rising Chinese demand, which got another big boost in 2008 when the Chinese government responded to the global crisis with a massive, credit-fueled stimulus. Investors in search of better yields than the paltry returns that US Treasuries and bank deposits offered saw an opportunity. Between 2011 and 2014, they lent $1.2 trillion to commodity producers, a quarter of it to US oil and gas companies.

That money financed a vast expansion of capacity. In 2014, energy, commodity and other materials companies plus related industries and utilities accounted for 60% worldwide capital spending (excluding finance and real estate), according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an international government-backed research group. All that began to reverse, first in 2013 when the Fed wound down its bond-buying and then in 2014 as it signaled it would raise rates in the coming year. Meanwhile, China slowed, and Saudi Arabia boosted oil production. Commodity prices tumbled, and both US shale companies and emerging-market companies suddenly found it far harder to borrow. Commodity-related investment slumped 16% globally last year, according to the OECD.

Those shockwaves helped send oil, emerging-market currencies and US stocks down late last year and earlier this year. Commodity prices have since stabilized, in large part because the Fed has foregone further rate increases. An actual financial crisis, similar to what swept through east and southeast Asia in 1997, has been avoided, largely because countries have floating currencies instead of pegs that must be defended with scarce reserves.

Another Fed rate increase wouldn’t have the same shock value as the first, but it would still push the dollar higher, putting renewed downward pressure on commodity prices since it makes the goods more expensive for other countries. It also would reignite capital flight from China and other emerging markets. Therefore, the Fed appears to be stuck in this negative feedback loop. Even if financial markets remain stable, the reversal of the commodity investment boom has “become and will remain a major headwind to world economic growth going forward,” the OECD says.

The world may have passed the most intense part of its adjustment, but that doesn’t mean the adjustment is over. It can take years for a bubble to deflate, and in the meantime, the Fed must be careful not to make it hurt more than is necessary. We believe that the Fed is aware of these fragilities, and is taking great care in making policy decisions. This likely means that interest rates will remain low for a longer period of time. Investors should have reasonable expectations for modest returns in this climate.

Comments are closed.